Co-production is an equal relationship between people who use services and the people responsible for services. They work together, from design to delivery, sharing strategic decision-making about policies as well as decisions about the best ways to deliver services.

(Think Local Act Personal, 2021, p. 364)

I was absolutely delighted that my presentation was chosen for the Steve Harrison Prize at the recent Health Politics and Policy Network’s Spring Event at The University of Manchester. In reading up on the namesake of this award I discovered that Steve Harrison wrote persuasively about the pitfalls of commodification in UK medicine. He highlighted the problem of standardised care which neglects the “social or psychological contexts” that contribute to ill health (2010, p. 192). The co-production of youth mental health services and patient and public engagement within health service research (the subject of my presentation) similarly challenges the position of standardised care, instead centring the lived expertise of patients through taking into account these social and psychological contexts. This alignment made the prize feel especially apt.

Presenting the results of the literature review to a specialist policy audience provoked questions for me about research ethics for patient and public involvement (PPI) work and finding the best ways of recognising the inputs from the young people involved in the project. This blog specifically explores whether there is a grey area between research data and PPI contributions and the ethical considerations around this. Though procedural ethics processes and committees ensure that relational ethics are addressed in research itself, how do we make sure that the people we work with are safe, are informed and give consent even when they are collaborators and co-researchers rather than research participants. The reflection uses the straightforward structure “What?, So What? Now What? based on the Model of Professional Thinking (Bannigan & Moores, 2009) to reflect on this.

What?

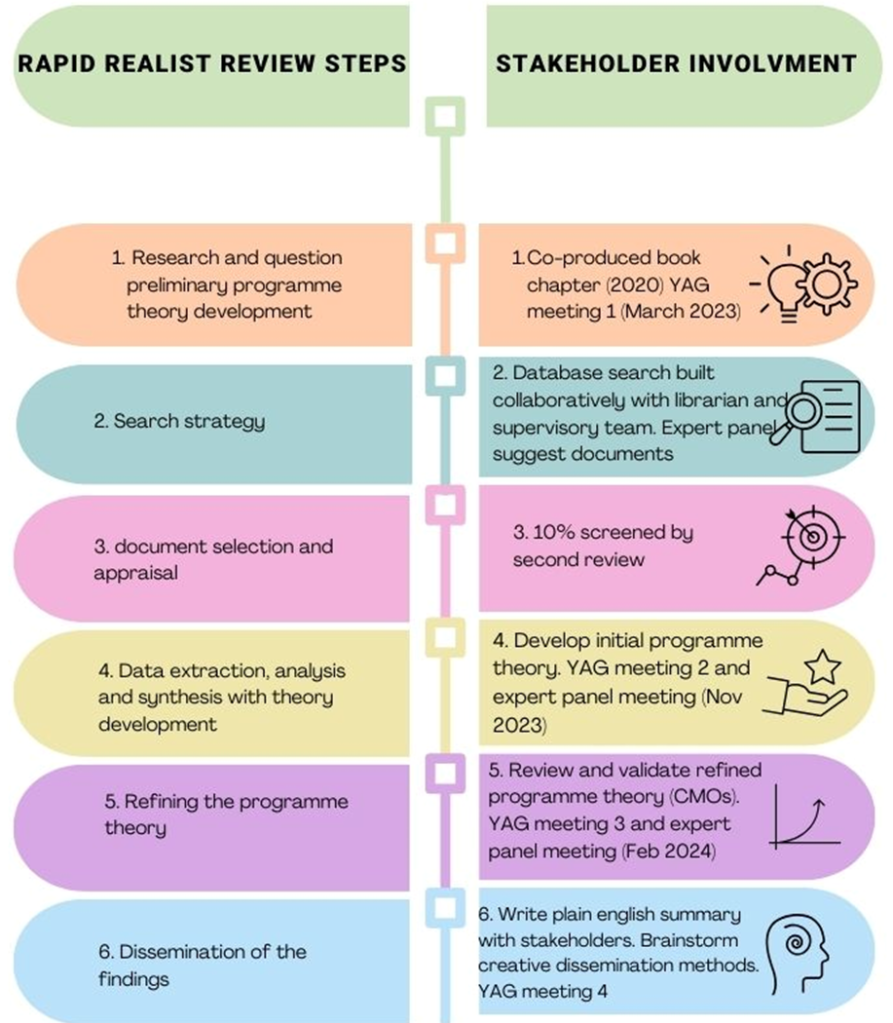

I met with expert stakeholders throughout the literature review process in eight workshops (see Figure 1). Most of these workshops were with young people from two advisory groups, though participation professionals and researchers in the field also contributed. The youth advisory groups are Think4Brum from the local NHS Trust Forward Thinking Birmingham (Think4Brum) and The University of Birmingham Institute of Mental Health Youth Advisory Group (IMH YAG) and their contributions included:

- defining the research question

- brainstorming ‘what works?’ / priorities for good co-production in this context

- sense-checking the theories emerging from the literature against their real-world experience

- suggesting papers to screen for inclusion alongside the database searches

- youth-proof readings of the study documents

- feeding back on the theory emerging from the literature review to refine a ‘final programme theory’ (Saul et al., 2013)

- identifying what was ‘missing’ or where they disagreed with the literature through considering rival theories

These contributions are subsequently shared outside of the PPI groups, either in the research outputs (e.g. the literature review itself, or the presentation under discussion here) or included in the next stage of the research (e.g. as items listed within the upcoming Delphi survey suggesting methods for effective co-production).

Figure 1: Stakeholder involvement throughout the review process

Graphic by Imaan Rathore, peer researcher.

So What?

These stakeholder workshops greatly impacted at every stage of the review including data collection, analysis/interpretation, and dissemination. To give one simple example of something which changed as a result of this stakeholder involvement, the youth advisory group suggested the word ‘adult’ in the final programme theory be replaced with ‘wider stakeholders’. This is for two reasons. Firstly, for this project ‘young people’ is defined according to the World Health Organisation definition of people aged 11-25 (WHO, 2021), so it is very possible to be both a ‘young person’ and an ‘adult’ in this context. Secondly, there may be people working within co-production programmes who are there in the role of ‘professional’ rather than young person but who also happen to fall into the youth age bracket. Numerous changes such as this were integrated into the interpretation and presentation of the results through the stakeholder workshops and this expert input is generally understood to be a strength of the work according to epistemic justice principles (Fricker, 2007).

Nevertheless, this process can create a grey area between the study data (extracted from the included literature) and these contributions from expert stakeholders within PPI roles. The main role for the youth advisory group is in study oversight and decision making about the direction of the research. However, their relevant lived experience also means they are well placed to sense-check the theories against “real-world” practice and this is explicitly their role as described in the rapid realist literature review process (Saul et al., 2013).

Although they were always informed of how their inputs will be used and are free to contribute or withdraw, this agreement isn’t as formal or explicit as it would be for research study participants. For example, research participants will have received a participant information sheet and signed a consent form. The inputs from PPI work does not require equivalent oversight or sign off from an ethical review committee, though of course local safeguarding procedures are in place.

On the one hand these young people are involved as collaborators, co-researchers or even project managers in their role within the advisory group, with a similar function to a trustee board. In this role it is essential that they have equitable access to the data extracted from the literature, decisions about the direction of the research and can support data interpretation and theory development. On the other hand, it should not be ignored that they are young people whose lived experience means they have the appropriate expertise to participate in this way and it is worth considering our duty of care to these young people in how we publish and acknowledge their contributions in a process which often relies on goodwill from all partners.

Now What?

To ensure that this ‘grey area’ is carefully considered for my PhD research I make frequent use of involvement guidelines, some examples are listed below:

- Involving young people in research work

- How to manage research and participation projects: The ethics according to young people

- The UK Standards for Public Involvement in Research

The key messages from these best practice guidelines are to: work alongside other stakeholders as partners, acknowledge their contributions, renumerate appropriately, work flexibly to meet the needs of participants and most importantly “have a clear authentic purpose for involving young people”(AYPH, 2021). We aim for all of these throughout the work. Though also knowing that we might not get everything right and so remaining open to reflect on lessons learned along the way. Overall, as described in no-nonsense terms by Wallcraft (2014), the grey area becomes clearer when you prioritise that the “involvement, participation, engagement, co-production, partnership, or whatever the currently fashionable phraseology happens to be” is genuine.

So, taking this opportunity to acknowledge the contributors, it is certain that without the support of these groups of young people and other workshop participants this literature review would have been much less rich, rigorous and relevant. Thank you to all those involved, and the prize is for all your hard work!

References

AYPH. (2021). Ethics in YP participation and research (Common Room, Issue. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://irp-cdn.multiscreensite.com/29f8e96e/files/uploaded/Ethics%20in%20YP%20participation%20and%20research%20CommonRoom.pdf

Bannigan, K., & Moores, A. (2009). A model of professional thinking: Integrating reflective practice and evidence based practice. Canadian journal of occupational therapy (1939), 76(5), 342-350. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740907600505

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

Harrison, S. (2010). Co‐Optation, Commodification and the Medical Model: Governing Uk Medicine since 1991. Public Administration, 87(2), 184-197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.01752.x

Saul, J. E., Willis, C. D., Bitz, J., & Best, A. (2013). A time-responsive tool for informing policy making: Rapid realist review. IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE, 8(103). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-103

Think Local Act Personal. (2021). Ladder of coproduction (T. L. A. Personal, Ed.). Social Care Institute for Excellence. https://www.thinklocalactpersonal.org.uk/Latest/Co-production-The-ladder-of-co-production/

Wallcraft, J. (2014). Foreword to National Involvement Partnership 4PIStandards for Involvement. In NSUN National Involvement Partnership Team (Ed.), National Involvement Partnership 4PIStandards for Involvement. https://www.nsun.org.uk/projects/4pi-involvement-standards/

WHO. (2021). Adolescent Mental Health (W. H. Organisation, Ed.) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health